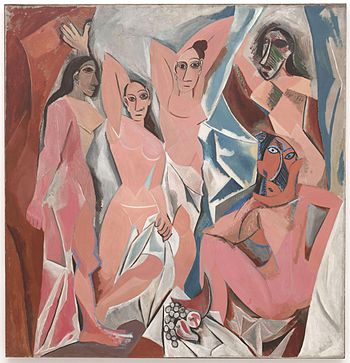

Les Demoiselles D'avignon Color Scheme

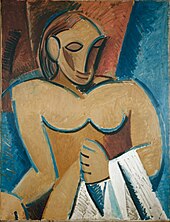

| Les Demoiselles d'Avignon | |

|---|---|

| English: The Ladies of Avignon | |

| |

| Artist | Pablo Picasso |

| Yr | 1907 |

| Medium | Oil on sail |

| Movement | Proto-Cubism |

| Dimensions | 243.9 cm × 233.seven cm (96 in × 92 in) |

| Location | Museum of Modern Fine art. Caused through the Lillie P. Bliss Bequest, New York Urban center[one] |

Les Demoiselles d'Avignon ( The Young Ladies of Avignon , originally titled The Brothel of Avignon )[2] is a large oil painting created in 1907 by the Castilian artist Pablo Picasso. The work, part of the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Fine art, portrays 5 nude female prostitutes in a brothel on Carrer d'Avinyó, a street in Barcelona, Kingdom of spain. Each figure is depicted in a disconcerting confrontational manner and none is conventionally feminine. The women announced slightly menacing and are rendered with angular and disjointed trunk shapes. The effigy on the left exhibits facial features and apparel of Egyptian or southern Asian style. The ii adjacent figures are shown in the Iberian way of Picasso's native Kingdom of spain, while the ii on the right are shown with African mask-similar features. The ethnic primitivism evoked in these masks, according to Picasso, moved him to "liberate an utterly original creative style of compelling, even savage force."[iii] [iv] [five]

In this adaptation of primitivism and abandonment of perspective in favor of a flat, ii-dimensional picture aeroplane, Picasso makes a radical deviation from traditional European painting. This proto-cubist work is widely considered to be seminal in the early development of both cubism and modern fine art.

Les Demoiselles was revolutionary and controversial and led to widespread acrimony and disagreement, even amongst the painter's closest associates and friends. Matisse considered the work something of a bad joke nevertheless indirectly reacted to it in his 1908 Bathers with a Turtle. Georges Braque too initially disliked the painting yet perhaps more than anyone else, studied the work in great detail. His subsequent friendship and collaboration with Picasso led to the cubist revolution.[half dozen] [seven] Its resemblance to Cézanne'southward The Bathers, Paul Gauguin's statue Oviri and El Greco's Opening of the 5th Seal has been widely discussed past later critics.

At the fourth dimension of its showtime exhibition in 1916, the painting was accounted immoral.[viii] The work, painted in Picasso's studio in the Bateau-Lavoir in Montmartre, Paris, was seen publicly for the start time at the Salon d'Antin in July 1916, at an exhibition organized by the poet André Salmon. It was at this exhibition that Salmon (who had previously titled the painting in 1912 Le bordel philosophique) renamed the work its current, less scandalous championship, Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, instead of the title originally chosen past Picasso, Le Bordel d'Avignon.[2] [vi] [ix] [10] Picasso, who always referred to it as monday bordel ("my brothel"),[8] or Le Bordel d'Avignon,[9] never liked Salmon'southward title and would accept instead preferred the bowdlerization Las chicas de Avignon ("The Girls of Avignon").[two]

Background and evolution [edit]

Picasso came into his ain as an of import artist during the first decade of the 20th century. He arrived in Paris from Espana around the turn of the century as a young, ambitious painter out to make a proper noun for himself. For several years he alternated between living and working in Barcelona, Madrid and the Castilian countryside, and fabricated frequent trips to Paris.

By 1904, he was fully settled in Paris and had established several studios, important relationships with both friends and colleagues. Between 1901 and 1904, Picasso began to achieve recognition for his Blue Period paintings. In the master these were studies of poverty and desperation based on scenes he had seen in Spain and Paris at the turn of the century. Subjects included gaunt families, blind figures, and personal encounters; other paintings depicted his friends, simply almost reflected and expressed a sense of blueness and despair.[11]

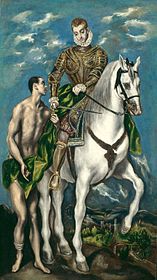

He followed his success by developing into his Rose Catamenia from 1904 to 1907, which introduced a strong element of sensuality and sexuality into his work. The Rose menstruation depictions of acrobats, circus performers and theatrical characters are rendered in warmer, brighter colors and are far more hopeful and joyful in their depictions of the maverick life in the Parisian avant-garde and its environment. The Rose period produced ii important big masterpieces: Family of Saltimbanques (1905), which recalls the piece of work of Gustave Courbet (1819–1877) and Édouard Manet (1832–1883); and Male child Leading a Horse (1905–06), which recalls Cézanne's Bather (1885–1887) and El Greco's Saint Martin and the Ragamuffin (1597–1599). While he already had a considerable following by the middle of 1906, Picasso enjoyed farther success with his paintings of massive oversized nude women, monumental sculptural figures that recalled the work of Paul Gauguin and showed his interest in archaic (African, Micronesian, Native American) art. He began exhibiting his work in the galleries of Berthe Weill (1865–1951) and Ambroise Vollard (1866–1939), quickly gaining a growing reputation and a post-obit amongst the creative communities of Montmartre and Montparnasse.[11]

Picasso became a favorite of the American art collectors Gertrude Stein and her brother Leo around 1905. The Steins' older blood brother Michael and his married woman Sarah also became collectors of his work. Picasso painted portraits of both Gertrude Stein and her nephew Allan Stein.[12]

Gertrude Stein began acquiring Picasso's drawings and paintings and exhibiting them in her informal Salon at her home in Paris. At one of her gatherings in 1905 he met Henri Matisse (1869–1954), who was to get in those days his chief rival, although in later on years a shut friend. The Steins introduced Picasso to Claribel Cone (1864–1929), and her sister Etta Cone (1870–1949), also American art collectors, who began to acquire Picasso and Matisse's paintings. Eventually Leo Stein moved to Italy, and Michael and Sarah Stein became of import patrons of Matisse, while Gertrude Stein continued to collect Picasso.[13]

Rivalry with Matisse [edit]

Henri Matisse, Le bonheur de vivre (1905–06), oil on canvas, 175 × 241 cm. Barnes Foundation, Merion, PA. A painting that was chosen Fauvist and brought Matisse both public derision and notoriety. Hilton Kramer wrote: "attributable to its long sequestration in the drove of the Barnes Foundation, which never permitted its reproduction in color, it is the least familiar of modern masterpieces. All the same this painting was Matisse's own response to the hostility his work had met with in the Salon d'Automne of 1905."[14]

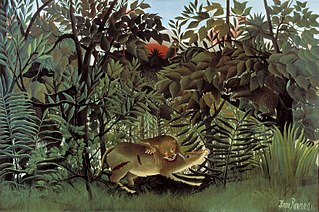

The Salon d'Automne of 1905 brought notoriety and attention to the works of Henri Matisse and the Les Fauves grouping. The latter gained their name after critic Louis Vauxcelles described their work with the phrase "Donatello chez les fauves" ("Donatello among the wild beasts"),[15] contrasting the paintings with a Renaissance-type sculpture that shared the room with them.[16] Henri Rousseau (1844–1910), an artist whom Picasso knew and admired and who was non a Fauve, had his big jungle scene The Hungry Panthera leo Throws Itself on the Antelope besides hanging near the works by Matisse and which may have had an influence on the detail sarcastic term used in the press.[17] Vauxcelles' comment was printed on 17 October 1905 in the daily paper Gil Blas, and passed into pop usage.[16] [xviii]

Although the pictures were widely derided—"A pot of paint has been flung in the face of the public", declared the critic Camille Mauclair (1872–1945)—they as well attracted some favorable attending.[sixteen] The painting that was singled out for the most attacks was Matisse'south Woman with a Hat; the purchase of this work by Gertrude and Leo Stein had a very positive consequence on Matisse, who was suffering demoralization from the bad reception of his work.[16]

Matisse's notoriety and preeminence as the leader of the new movement in modern painting connected to build throughout 1906 and 1907, and Matisse attracted a following of artists including Georges Braque (1880–1963), André Derain (1880–1954), Maurice de Vlaminck (1876–1958). Picasso's work had passed through his Blue menstruum and his Rose period and while he had a considerable following his reputation was tame in comparing to his rival Matisse. The larger theme of Matisse's influential Le bonheur de vivre, an exploration of "The Golden Age", evokes the historic "Ages of Homo" theme and the potentials of a provocative new age that the twentieth century era offered. An every bit bold, similarly themed painting titled The Gilt Age, completed by Derain in 1905, shows the transfer of human ages in an fifty-fifty more than straight way.[nineteen]

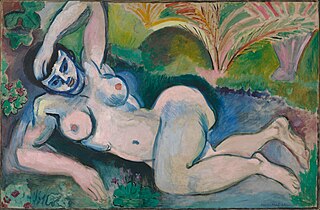

Matisse and Derain shocked the French public once again at the March 1907 Société des Artistes Indépendants when Matisse exhibited his painting Blue Nude and Derain contributed The Bathers. Both paintings evoke ideas of human origins (globe beginnings, evolution) an increasingly important theme in Paris at this time.[19] The Blueish Nude was 1 of the paintings that would later create an international sensation at the Arsenal Show of 1913 in New York City.[20]

From October 1906 when he began preparatory work for Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, until its completion in March 1907, Picasso was vying with Matisse to be perceived as the leader of Modernistic painting. Upon its completion the shock and the bear on of the painting propelled Picasso into the eye of controversy and all only knocked Matisse and Fauvism off the map, virtually ending the motility by the following year. In 1907 Picasso joined the art gallery that had recently been opened in Paris by Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler (1884–1979). Kahnweiler was a German art historian and collector who became one of the premier French art dealers of the 20th century. He became prominent in Paris beginning in 1907 for being among the showtime champions of Picasso, and specially his painting Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. Before 1910 Picasso was already being recognized every bit one of the of import leaders of Mod art alongside Henri Matisse, who had been the undisputed leader of Fauvism and who was more than ten years older than he, and his contemporaries the Fauvist André Derain and the former Fauvist and swain Cubist, Georges Braque.[21]

In his 1992 essay Reflections on Matisse, the art critic Hilton Kramer wrote,

After the bear on of Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, however, Matisse was never again mistaken for an avant-garde incendiary. With the bizarre painting that appalled and electrified the cognoscenti, which understood the Les Demoiselles was at in one case a response to Matisse's Le bonheur de vivre (1905–1906) and an assail upon the tradition from which it derived, Picasso effectively appropriated the function of avant-garde wild beast—a role that, as far as public opinion was concerned, he was never to relinquish.[22]

Kramer goes on to say,

Whereas Matisse had drawn upon a long tradition of European painting—from Giorgione, Poussin, and Watteau to Ingres, Cézanne, and Gauguin—to create a mod version of a pastoral paradise in Le bonheur de vivre, Picasso had turned to an alien tradition of primitive fine art to create in Les Demoiselles a netherworld of foreign gods and vehement emotions. As between the mythological nymphs of Le bonheur de vivre and the grotesque effigies of Les Demoiselles, there was no question as to which was the more shocking or more intended to exist shocking. Picasso had unleashed a vein of feeling that was to take immense consequences for the art and culture of the modernistic era while Matisse's appetite came to seem, as he said in his Notes of a Painter, more limited—limited that is, to the realm of aesthetic pleasure. There was thus opened up, in the very outset decade of the century and in the work of its two greatest artists, the chasm that has connected to split up the art of the modern era downward to our ain time.[23]

Influences [edit]

Picasso created hundreds of sketches and studies in training for the final work.[9] [24] He long acknowledged the importance of Castilian art and Iberian sculpture as influences on the painting. The work is believed by critics to be influenced by African tribal masks and the art of Oceania, although Picasso denied the connection; many art historians remain skeptical about his denials. Picasso spent an Oct 1906 evening closely studying a Teke figure from Congo then endemic by Matisse. Information technology was later that dark that Picasso'southward starting time studies for what would go Les Demoiselles d'Avignon were created.[19] Several experts maintain that, at the very least, Picasso visited the Musée d'Ethnographie du Trocadéro (known later on as the Musée de l'Homme) in the spring of 1907 where he saw and sought inspiration from African and other arts shortly before completing Les Demoiselles. [25] [26] He had come up to this museum originally to study plaster casts of medieval sculptures, and then also considered examples of "archaic" art.[19]

El Greco [edit]

Pablo Picasso, Nus (Nudes), 1905, graphite on paper

El Greco's paintings, such as this Apocalyptic Vision of Saint John, have been suggested as a source of inspiration for Picasso leading up to Les Demoiselles d' Avignon.[11]

In 1907, when Picasso began piece of work on Les Demoiselles, one of the quondam master painters he greatly admired was El Greco (1541–1614), who at the time was largely obscure and under-appreciated. Picasso'south friend Ignacio Zuloaga (1870–1945) caused El Greco's masterpiece, the Opening of the 5th Seal, in 1897 for g pesetas.[27] [28] The relation between Les Demoiselles d'Avignon and the Opening of the Fifth Seal was pinpointed in the early 1980s, when the stylistic similarities and the relationship between the motifs and visually identifying qualities of both works were analyzed.[29] [xxx]

El Greco'due south painting, which Picasso studied repeatedly in Zuloaga'south business firm, inspired non simply the size, format, and composition of Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, but also its apocalyptic power.[31] Afterward, speaking of the work to Dor de la Souchère in Antibes, Picasso said: "In any case, merely the execution counts. From this point of view, it is right to say that Cubism has a Spanish origin and that I invented Cubism. Nosotros must expect for the Spanish influence in Cézanne. Things themselves necessitate it, the influence of El Greco, a Venetian painter, on him. Merely his structure is Cubist."[32]

The relationship of the painting to other grouping portraits in the Western tradition, such as Diana and Callisto by Titian (1488–1576), and the same subject by Rubens (1577–1640), in the Prado, has besides been discussed.[33]

Cézanne and Cubism [edit]

Both Paul Gauguin (1848–1903) and Paul Cézanne (1839–1906) were accorded major posthumous retrospective exhibitions at the Salon d'Automne in Paris between 1903 and 1907, and both were of import influences on Picasso and instrumental to his creation of Les Demoiselles. According to the English fine art historian, collector and author of The Cubist Epoch, Douglas Cooper, both of those artists were particularly influential to the formation of Cubism and especially important to the paintings of Picasso during 1906 and 1907.[34] Cooper goes on to say still Les Demoiselles is oftentimes erroneously referred to as the get-go Cubist painting. He explains,

The Demoiselles is generally referred to every bit the first Cubist flick. This is an exaggeration, for although it was a major first step towards Cubism information technology is not all the same Cubist. The disruptive, expressionist element in it is even reverse to the spirit of Cubism, which looked at the earth in a detached, realistic spirit. Nevertheless, the Demoiselles is the logical pic to take as the starting point for Cubism, because it marks the birth of a new pictorial idiom, because in it Picasso violently overturned established conventions and because all that followed grew out of it.[35]

Although not well known to the general public prior to 1906, Cézanne's reputation was highly regarded in avant-garde circles, as evidenced by Ambroise Vollard'south interest in showing and collecting his work, and past Leo Stein's interest. Picasso was familiar with much of Cézanne's work that he saw at Vollard's gallery and at the Stein's. Subsequently Cézanne died in 1906, his paintings were exhibited in Paris in a large scale museum-like retrospective in September 1907. The 1907 Cézanne retrospective at the Salon d'Automne greatly impacted the direction that the avant-garde in Paris took, lending credence to his position as one of the most influential artists of the 19th century and to the advent of Cubism. The 1907 Cézanne exhibition was enormously influential in establishing Cézanne equally an important painter whose ideas were particularly resonant especially to young artists in Paris.[eleven] [36]

Both Picasso and Braque constitute the inspiration for their proto-Cubist works in Paul Cézanne, who said to observe and learn to see and treat nature equally if it were equanimous of basic shapes similar cubes, spheres, cylinders, and cones. Cézanne's explorations of geometric simplification and optical phenomena inspired Picasso, Braque, Metzinger, Gleizes, Robert Delaunay, Le Fauconnier, Gris and others to experiment with ever more complex multiple views of the same subject, and, eventually to the fracturing of form. Cézanne thus sparked one of the almost revolutionary areas of artistic research of the 20th century, one which was to touch on profoundly the development of modern art.[36]

Gauguin and Primitivism [edit]

Gauguin, 1894, Oviri (Sauvage), partially glazed stoneware, 75 × 19 × 27 cm, Musée d'Orsay, Paris

Pablo Picasso'due south paintings of monumental figures from 1906 were direct influenced by Gauguin. The savage power evoked by Gauguin's work led directly to Les Demoiselles in 1907.[37]

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the European cultural elite were discovering African, Oceanic and Native American art. Artists such as Paul Gauguin, Henri Matisse and Picasso were intrigued and inspired by the stark ability and simplicity of styles of those cultures. Around 1906, Picasso, Matisse, Derain and other artists in Paris had acquired an interest in primitivism, Iberian sculpture,[38] African art and tribal masks, in role because of the compelling works of Paul Gauguin that had of a sudden achieved heart phase in the advanced circles of Paris. Gauguin's powerful posthumous retrospective exhibitions at the Salon d'Automne in Paris in 1903[39] and an fifty-fifty larger one in 1906[twoscore] had a stunning and powerful influence on Picasso's paintings.[eleven]

In the autumn of 1906, Picasso followed his previous successes with paintings of oversized nude women, and monumental sculptural figures that recalled the piece of work of Paul Gauguin and showed his interest in primitive fine art. Pablo Picasso's paintings of massive figures from 1906 were directly influenced by Gauguin'south sculpture, painting and his writing likewise. The barbarous power evoked by Gauguin's work lead directly to Les Demoiselles in 1907.[xi]

According to Gauguin biographer David Sweetman, Pablo Picasso as early on as 1902 became an addict of Gauguin'south piece of work when he met and befriended the departer Spanish sculptor and ceramist Paco Durrio, in Paris. Durrio had several of Gauguin'due south works on manus because he was a friend of Gauguin'south and an unpaid agent of his piece of work. Durrio tried to help his poverty-stricken friend in Tahiti past promoting his oeuvre in Paris. Afterwards they met Durrio introduced Picasso to Gauguin's stoneware, helped Picasso brand some ceramic pieces and gave Picasso a first La Plume edition of Noa Noa: The Tahiti Journal of Paul Gauguin. [41]

Concerning Gauguin'southward bear on on Picasso, fine art historian John Richardson wrote,

The 1906 exhibition of Gauguin's work left Picasso more ever in this artist's thrall. Gauguin demonstrated the most disparate types of art—non to speak of elements from metaphysics, ethnology, symbolism, the Bible, classical myths, and much else besides—could exist combined into a synthesis that was of its fourth dimension notwithstanding timeless. An creative person could also confound conventional notions of dazzler, he demonstrated, by harnessing his demons to the dark gods (not necessarily Tahitian ones) and borer a new source of divine energy. If in later years Picasso played downwardly his debt to Gauguin, at that place is no doubt that between 1905 and 1907 he felt a very close kinship with this other Paul, who prided himself on Spanish genes inherited from his Peruvian grandmother. Had not Picasso signed himself 'Paul' in Gauguin's honor.[42]

Both David Sweetman and John Richardson point to Gauguin'southward Oviri (literally meaning 'savage'), a gruesome phallic representation of the Tahitian goddess of life and death intended for Gauguin'southward grave. Kickoff exhibited in the 1906 retrospective, it was likely a direct influence on Les Demoiselles. Sweetman writes,

Gauguin'due south statue Oviri, which was prominently displayed in 1906, was to stimulate Picasso's interest in both sculpture and ceramics, while the woodcuts would reinforce his interest in print-making, though it was the chemical element of the primitive in all of them which well-nigh conditioned the direction that Picasso's art would take. This interest would culminate in the seminal Les Demoiselles d'Avignon.[43]

According to Richardson,

Picasso's interest in stoneware was farther stimulated by the examples he saw at the 1906 Gauguin retrospective at the Salon d'Automne. The most disturbing of those ceramics (one that Picasso might have already seen at Vollard'southward) was the gruesome Oviri. Until 1987, when the Musée d'Orsay caused this piddling-known work (exhibited only once since 1906) information technology had never been recognized as the masterpiece it is, let alone recognized for its relevance to the works leading up to the Demoiselles. Although just under 30 inches high, Oviri has an crawly presence, as befits a monument intended for Gauguin's grave. Picasso was very struck by Oviri. 50 years afterward he was delighted when [Douglas] Cooper and I told him that we had come upon this sculpture in a collection that as well included the original plaster of his Cubist head. Has it been a revelation, like Iberian sculpture? Picasso's shrug was grudgingly affirmative. He was e'er loath to admit Gauguin'due south role in setting him on the road to primitivism.[44]

African and Iberian art [edit]

Female musician from the "Relief of Osuna", Iberian, ca. 200 BC

Iberian female sculpture from third or 2nd century BC

This way influenced Les Demoiselles d'Avignon.

During the 19th and 20th centuries, Europe's colonization of Africa led to many economic, social, political, and even artistic encounters. From these encounters, Western visual artists became increasingly interested in the unique forms of African art, peculiarly masks from the Niger-Congo region. In an essay by Dennis Duerden, author of African Art (1968), The Invisible Present (1972), and a quondam manager of the BBC World Service, the mask is defined every bit "very oft a consummate head-dress and not only that part that conceals the face".[45] This form of visual art and paradigm appealed to Western visual artists, leading to what Duerden calls the "discovery" of African fine art by Western practitioners, including Picasso.

African Fang mask similar in style to those Picasso saw in Paris just prior to painting Les Demoiselles d'Avignon

The stylistic sources for the heads of the women and their degree of influence has been much discussed and debated, in particular the influence of African tribal masks, art of Oceania,[46] and pre-Roman Iberian sculptures. The rounded contours of the features of the three women to the left tin be related to Iberian sculpture, but not manifestly the fragmented planes of the two on the right, which indeed seem influenced by African masks.[47] Lawrence Weschler says that,

in many ways, much of the moldering cultural and fifty-fifty scientific ferment that characterized the first decade and a half of the twentieth century and that laid the foundations for much of what we today consider modern tin exist traced dorsum to ways in which Europe was already wrestling with its bad-faith, oftentimes strenuously repressed, cognition of what it had been doing in Africa. The example of Picasso near launching cubism with his 1907 Desmoiselles d'Avignon, in response to the sorts of African masks and other colonial haul he was encountering in Paris's Musee de 50'Homme, is obvious.[5]

Congo masks published past Leo Frobenius in his 1898 book Die Masken und Geheimbunde Afrika

Individual collections and illustrated books featuring African art in this period were also important. While Picasso emphatically denied the influence of African masks on the painting: "African art? Never heard of it!" (L'art nègre? Connais pas!),[9] [48] this is belied by his deep interest in the African sculptures owned by Matisse and his close friend Guiliaume Apollinaire.[19] Since none of the African masks once thought to have influenced Picasso in this painting were available in Paris at the time work was painted, he is thought now to have studied African mask forms in an illustrated volume past anthropologist Leo Frobenius.[19] Primitivism continues in his work during, earlier and after the painting of Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, from spring 1906 through the bound of 1907. Influences from ancient Iberian sculpture are also important.[xi] [49] Some Iberian reliefs from Osuna, then only recently excavated, were on display in the Louvre from 1904. Archaic Greek sculpture has also been claimed as an influence.

The influence of African sculpture became an outcome in 1939, when Alfred Barr claimed that the primitivism of the Demoiselles derived from the fine art of Côte d'Ivoire and the French Congo.[50] Picasso insisted that the editor of his catalogue raissonne, Christian Zervos, publish a disclaimer: the Demoiselles, he said, owed zippo to African art, everything to the reliefs from Osuna that he had seen in the Louvre a year or so earlier.[51] Even so, he is known to accept seen African tribal masks while working on the painting, during a visit to the Ethnographic Museum of the Trocadero with Andre Malraux in March 1907, most which he later said "When I went to the Trocadero, it was disgusting. The flea market, the smell. I was all alone. I wanted to become away, but I didn't leave. I stayed, I stayed. I understood that it was very of import. Something was happening to me, right. The masks weren't like whatsoever other pieces of sculpture, not at all. They were magic things."[9] [52] [53] Maurice de Vlaminck is often credited with introducing Picasso to African sculpture of Fang extraction in 1904.[54]

Picasso biographer John Richardson recounts in A Life of Picasso, The Cubist Insubordinate 1907–1916, art dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler's recollection of his starting time visit to Picasso'due south studio in July 1907. Kahnweiler remembers seeing "dusty stacks of canvases" in Picasso'due south studio and "African sculptures of majestic severity". Richardson comments: "and then much for Picasso'southward story that he was not withal enlightened of Tribal fine art.'"[55] A photograph of Picasso in his studio surrounded past African sculptures c.1908, is found on folio 27 of that same volume.[56]

Suzanne Preston Blier says that, like Gauguin and several other artists in this era, Picasso used illustrated books for many of his preliminary studies for this painting. In improver to the Frobenius volume, his sources included a 1906 publication of a 12th-century Medieval art manuscript on architectural sculpture by Villiard de Honnecourt and a book by Carl Heinrich Stratz of pseudo-pornography showing photos and drawings of women from around the world organized to evoke ideas of homo origins and evolution. Blier suggests that this helps account for the diversity of styles Picasso employed in his epitome-filled sketchbooks for this painting. These books, and other sources such as cartoons, Blier writes, also offer hints as to the larger meaning of this painting.[19]

Mathematics [edit]

An illustration from Jouffret's Traité élémentaire de géométrie à quatre dimensions. The book, which influenced Picasso, was given to him by Princet.

Maurice Princet,[57] a French mathematician and actuary, played a part in the nativity of Cubism as an associate of Pablo Picasso, Guillaume Apollinaire, Max Jacob, Jean Metzinger, Robert Delaunay, Juan Gris and later Marcel Duchamp. Princet became known as "le mathématicien du cubisme" ("the mathematician of cubism").[58] [59]

Princet is credited with introducing the work of Henri Poincaré and the concept of the "fourth dimension" to artists at the Bateau-Lavoir.[60] Princet brought to the attention of Picasso, Metzinger and others, a book by Esprit Jouffret, Traité élémentaire de géométrie à quatre dimensions (Elementary Treatise on the Geometry of Four Dimensions, 1903),[61] a popularization of Poincaré's Scientific discipline and Hypothesis in which Jouffret described hypercubes and other complex polyhedra in four dimensions and projected them onto the ii-dimensional surface. Picasso'southward sketchbooks for Les Demoiselles d'Avignon illustrate Jouffret's influence on the artist's work.[62]

Touch [edit]

Although Les Demoiselles had an enormous and profound influence on mod art, its impact was not firsthand, and the painting stayed in Picasso's studio for many years. At showtime, only Picasso'due south intimate circle of artists, dealers, collectors and friends were aware of the work. Soon later the late summer of 1907, Picasso and his long-fourth dimension lover Fernande Olivier (1881–1966) had a parting of the means. The re-painting of the two heads on the far right of Les Demoiselles fueled speculation that information technology was an indication of the split between Picasso and Olivier. Although they later reunited for a catamenia, the relationship concluded in 1912.[63]

A photograph of the Les Demoiselles was start published in an commodity past Gelett Burgess entitled "The Wild Men of Paris, Matisse, Picasso and Les Fauves", The Architectural Tape, May 1910.[64]

Les Demoiselles would non be exhibited until 1916, and non widely recognized as a revolutionary accomplishment until the early 1920s, when André Breton (1896–1966) published the work.[24] The painting was reproduced once more in Cahiers d'fine art (1927), within an commodity dedicated to African art.[65]

Richardson goes on to say that Matisse was fighting mad upon seeing the Demoiselles at Picasso'southward studio. He permit it be known that he regarded the painting as an attempt to ridicule the modern motility; he was outraged to observe his sensational Blue Nude, not to speak of Bonheur de vivre, overtaken by Picasso'south "hideous" whores. He vowed to become fifty-fifty and make Picasso beg for mercy. But equally the Bonheur de vivre had fueled Picasso'due south competitiveness, Les Demoiselles now fueled Matisse'southward.[66]

Among Picasso'south closed circle of friends and colleagues there was a mixture of opinions about Les Demoiselles. Georges Braque and André Derain were both initially troubled by it although they were supportive of Picasso. Co-ordinate to William Rubin, ii of Picasso's friends, the fine art critic André Salmon and the painter Ardengo Soffici (1879–1964), were enthusiastic well-nigh information technology while Guillaume Apollinaire (1880–1918) wasn't. Both the art dealer-collector Wilhelm Uhde (1874–1947), and Kahnweiler were more enthusiastic nearly the painting however.[67]

Co-ordinate to Kahnweiler Les Demoiselles was the outset of Cubism. He writes:

Early in 1907 Picasso began a strange big painting depicting women, fruit and mantle, which he left unfinished. Information technology cannot be called other than unfinished, fifty-fifty though it represents a long period of piece of work. Begun in the spirit of the works of 1906, it contains in one department the endeavors of 1907 and thus never constitutes a unified whole.

The nudes, with large, quiet eyes, stand up rigid, like mannequins. Their stiff, round bodies are flesh-colored, blackness and white. That is the way of 1906.

In the foreground, however, alien to the style of the rest of the painting, appear a crouching figure and a bowl of fruit. These forms are fatigued angularly, not roundly modeled in chiaroscuro. The colors are luscious blue, strident yellow, next to pure black and white. This is the kickoff of Cubism, the starting time upsurge, a drastic titanic clash with all of the bug at one time.

—Kahnweiler, 1920[68]

Public view and title [edit]

From 16 to 31 July 1916 Les Demoiselles was exhibited to the public for the get-go time at the Salon d'Antin, an exhibition organized past André Salmon titled L'Art moderne en France. The exhibition space at 26 rue d'Antin was lent by the famous couturier and art collector Paul Poiret. The larger Salon d'Automne and Salon des Indépendants had been airtight due to World War I, making this the just Cubists' exhibition in France since 1914.[69] On 23 July 1916 a review was published in Le Cri de Paris:[seventy]

The Cubists are not waiting for the war to finish to recommence hostilities confronting good sense. They are exhibiting at the Galerie Poiret naked women whose scattered parts are represented in all iv corners of the sail: here an heart, there an ear, over there a manus, a foot on pinnacle, a mouth beneath. M. Picasso, their leader, is peradventure the least disheveled of the lot. He has painted, or rather daubed, five women who are, if the truth be told, all hacked upwardly, and nevertheless their limbs somehow manage to hold together. They have, moreover, piggish faces with eyes wandering negligently above their ears. An enthusiastic art-lover offered the artist xx,000 francs for this masterpiece. One thousand. Picasso wanted more. The fine art-lover did not insist.[69] [seventy]

Picasso referred to his just entry at the Salon d'Antin as his Brothel painting calling it Le Bordel d'Avignon only André Salmon who had originally labeled the piece of work, Le Bordel Philosophique, retitled it Les Demoiselles d'Avignon so equally to lessen its scandalous bear upon on the public. Picasso never liked the title, however, preferring "las chicas de Avignon", but Salmon's championship stuck.[ii] Leo Steinberg labels his essays on the painting afterward its original title. Co-ordinate to Suzanne Preston Blier, the word bordel in the painting'due south title, rather than evoking a house of prostitution (une maison close) instead more than accurately references in French a complex situation or mess. This painting, Blier says, explores not prostitution per se, but instead sex and motherhood more mostly, along with the complexities of evolution in the colonial multi-racial world. The name Avignon, scholars debate,[ who? ] non merely references the street where Picasso once bought his paint supplies (which had a few brothels), but also the habitation of Max Jacob's grandmother, whom Picasso jocularly identifies as i of the painting's diverse modern day subjects.[19]

The merely other time the painting might have been exhibited to the public prior to a 1937 showing in New York was in 1918, in an exhibition dedicated to Picasso and Matisse at Galerie Paul Guillaume in Paris, though very little data exists about this exhibition or the presence (if at all) of Les Demoiselles.[69]

Later, the painting was rolled up and remained with Picasso until 1924 when, with urging and help from Breton and Louis Aragon (1897–1982), he sold it to designer Jacques Doucet (1853–1929), for 25,000 francs.[71] [72]

Interpretation [edit]

Pablo Picasso, Head of a Sleeping Woman (Study for Nude with Mantle), 1907, oil on canvas, 61.4 × 47.6 cm, The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Picasso drew each of the figures in Les Demoiselles differently. The woman pulling the curtain on the upper right is rendered with heavy paint. Composed of sharp geometric shapes, her head is the most strictly Cubist of all 5.[73] The curtain seems to blend partially into her body. The Cubist caput of the crouching figure (lower right) underwent at least two revisions from an Iberian figure to its current country. She also seems to have been drawn from two unlike perspectives at once, creating a confusing, twisted figure. The woman above her is rather manly, with a dark face and square breast. The whole picture is in a two-dimensional manner, with an abandoned perspective.

Pablo Picasso, Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, item of the figure to the upper right

Pablo Picasso, Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, item of the figure to the lower right

Pablo Picasso, Nu aux bras levés (Nude), 1907

Pablo Picasso, 1907, Nu à la serviette, oil on sail, 116 10 89 cm

Pablo Picasso, 1907, Femme nue, oil on canvas, 92 x 43 cm, Museo delle Civilization, Milano

Much of the critical debate that has taken place over the years centers on attempting to account for this multiplicity of styles inside the work. The dominant understanding for over 5 decades, espoused most notably by Alfred Barr, the get-go director of the Museum of Modern Fine art in New York City and organizer of major career retrospectives for the creative person, has been that it tin be interpreted as show of a transitional catamenia in Picasso's art, an endeavor to connect his earlier piece of work to Cubism, the fashion he would assist invent and develop over the next five or six years.[ane] Suzanne Preston Blier says that the divergent styles of the painting were added intentionally to convey to each women art "fashion" attributes from the five geographic areas each woman represents.[nineteen]

Art critic John Berger, in his controversial 1965 biography The Success and Failure of Picasso,[74] interprets Les Demoiselles d'Avignon as the provocation that led to Cubism:

Blunted by the insolence of so much recent art, nosotros probably tend to underestimate the brutality of the Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. All his friends who saw it in his studio were at beginning shocked past it. And it was meant to shock…

A brothel may not in itself be shocking. Just women painted without charm or sadness, without irony or social comment, women painted like the palings of a stockade through eyes that look out every bit if at expiry – that is shocking. And equally the method of painting. Picasso himself has said that he was influenced at the time by archaic Spanish (Iberian) sculpture. He was also influenced – particularly in the two heads at the correct – by African masks…here it seems that Picasso's quotations are simple, direct, and emotional. He is not in the least concerned with formal problems. The dislocations in this picture are the result of aggression, not aesthetics; it is the nearest you can get in a painting to an outrage…

I emphasize the fierce and iconoclastic attribute of this painting considering it is usually enshrined every bit the great formal exercise which was the starting indicate of Cubism. It was the starting point of Cubism, in so far as it prompted Braque to begin painting at the terminate of the year his own far more formal reply to Les Demoiselles d'Avignon…however if he had been left to himself, this flick would never have led Picasso to Cubism or to any style of painting remotely resembling it…It has nothing to do with that twentieth-century vision of the future which was the essence of Cubism.

Yet it did provoke the kickoff of the smashing period of exception in Picasso'southward life. Nobody can know exactly how the change began within Picasso. We can only note the results. Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, different any previous painting by Picasso, offers no evidence of skill. On the contrary, it is clumsy, overworked, unfinished. It is as though his fury in painting it was and so great that it destroyed his gifts…

By painting Les Demoiselles d'Avignon Picasso provoked Cubism. Information technology was the spontaneous and, every bit ever, primitive insurrection out of which, for good historical reasons, the revolution of Cubism developed.[74]

In 1972, art critic Leo Steinberg in his essay The Philosophical Brothel posited a wholly different explanation for the wide range of stylistic attributes. Using the before sketches—which had been ignored past most critics—he argued that far from evidence of an creative person undergoing a rapid stylistic metamorphosis, the diverseness of styles tin be read as a deliberate attempt, a careful program, to capture the gaze of the viewer. He notes that the five women all seem eerily disconnected, indeed wholly unaware of each other. Rather, they focus solely on the viewer, their divergent styles just furthering the intensity of their glare.[one]

The earliest sketches feature two men inside the brothel; a sailor and a medical student (who was oftentimes depicted belongings either a volume or a skull, causing Barr and others to read the painting every bit a memento mori, a reminder of decease). A trace of their presence at a tabular array in the center remains: the jutting edge of a tabular array most the bottom of the canvass. The viewer, Steinberg says, has come to replace the sitting men, forced to face up the gaze of prostitutes head on, invoking readings far more than complex than a elementary allegory or the autobiographical reading that attempts to sympathise the work in relation to Picasso'south ain history with women. A globe of meanings then becomes possible, suggesting the piece of work every bit a meditation on the danger of sex, the "trauma of the gaze" (to utilise a phrase of Rosalind Krauss'southward invention), and the threat of violence inherent in the scene and sexual relations at big.[one]

According to Steinberg, the reversed gaze, that is, the fact that the figures look directly at the viewer, as well as the idea of the cocky-possessed woman, no longer there solely for the pleasure of the male gaze, may exist traced back to Manet's Olympia of 1863.[one] William Rubin (1927–2006), the old Managing director of the Department of Painting and Sculpture at MoMA wrote that "Steinberg was the start author to come up to grips with the sexual discipline of the Demoiselles."[75]

A few years after writing The Philosophical Brothel, Steinberg wrote farther about the revolutionary nature of Les Demoiselles:

Picasso was resolved to undo the continuities of course and field which Western art had so long taken for granted. The famous stylistic rupture at right turned out to exist merely a consummation. Overnight, the contrived coherences of representational art - the feigned unities of time and place, the stylistic consistencies - all were alleged to be fictional. The Demoiselles confessed itself a picture conceived in duration and delivered in spasms. In this one piece of work Picasso discovered that the demands of discontinuity could be met on multiple levels: by cleaving depicted flesh; by elision of limbs and abridgement; past slashing the web of connecting infinite; by sharp changes of vantage; and by a sudden stylistic shift at the climax. Finally, the insistent staccato of the presentation was found to intensify the moving-picture show'south address and symbolic charge: the beholder, instead of observing a roomfuI of lazing whores, is targeted from all sides. And so far from suppressing the subject field, the mode of organization heightens its flagrant eroticism.[76]

At the stop of the first volume of his (so far) three book Picasso biography: A Life Of Picasso. The Prodigy, 1881–1906, John Richardson comments on Les Demoiselles. Richardson says:

It is at this indicate, the beginning of 1907, that I propose to bring this outset volume to an cease. The 25-year-quondam Picasso is nearly to conjure up a quintet of Dionysiac Demoiselles on his huge new canvass. The execution of this painting would brand a dramatic climax to these pages. However, it would imply that Picasso's smashing revolutionary piece of work constitutes a decision to all that has gone earlier. It does not. For all that the Demoiselles is rooted in Picasso's by, not to speak of such precursors every bit the Iron Age Iberians, El Greco, Gauguin and Cézanne, it is essentially a beginning: the most innovative painting since Giotto. As nosotros will run across in the next volume, it established a new pictorial syntax; it enabled people to perceive things with new optics, new minds, new awareness. Les Demoiselles d'Avignon is the kickoff unequivocally 20th-century masterpiece, a primary detonator of the modernistic movement, the cornerstone of 20th-century art. For Picasso it would also be a rite of passage: what he called an exorcism.' Information technology cleared the style for cubism. Information technology besides banished the creative person's demons. Afterwards, these demons would return and require farther exorcism. For the next decade, however, Picasso would feel as gratis and creative and 'every bit overworked' as God.[77]

Suzanne Preston Blier addresses the history and meaning of Les Demoiselles d'Avignon in a 2019 book in a different way, one that draws on her African art expertise and an array of newly discovered sources she unearthed. Blier addresses the painting not as a simple bordello scene only every bit Picasso's interpretation of the diversity of women from around the globe that Picasso encountered in part through photographs and sculptures seen in illustrated books. These representations, Blier argues, are primal to agreement the painting's cosmos and aid identify the demoiselles every bit global figures – mothers, grandmothers, lovers, and sisters, living the colonial world Picasso inhabited. She says that Picasso has reunited these various women together in this strange cavern-like (and womb-resembling) setting as a kind of global "fourth dimension machine" – each woman referencing a different era, identify of origins, and concomitant artistic mode, as function of the broader ages of man them of import to the new century, in which core themes of evolution took on an increasingly important role. The ii men (a sailor and a doctor) depicted in some of the painting's before preparatory drawings, Blier suggests, likely correspond the male authors of two of the illustrated books that Picasso employed – the anthropologist Leo Frobenius as sailor, one travels the world to. explore various ports of call and the Vienna medical doctor, Karl Heinrich Stratz who holds a human skull or volume consequent with the detailed anatomical studies that he provides.[19]

Blier is able to date the painting to late March 1907 directly following the opening of the Salon des Independents where Matisse and Derain had exhibited their own bold, emotionally charged "origins"-themed tableaux. The large scale of the sail, Blier says, complements the of import scientific and historical theme. The reunion of the mothers of each "race" inside this human being evolutionary framework, Blier maintains, besides constitutes the larger "philosophy" behind the painting's original le bordel philosophique title – evoking the potent "mess" and "complex state of affairs" (le bordel) that Picasso was exploring in this work. In contrast to Leo Steinberg and William Rubin who argued that Picasso had effaced the two right hand demoiselles to repaint their faces with African masks in response to a crisis stemming from larger fears of death or women, an early on photograph of the painting in Picasso'south studio, Blier shows, indicates that the artist had portrayed African masks on these women from the outset consistent with their identities as progenitors of these races. Blier argues that the painting was largely completed in a unmarried night following a fence almost philosophy with friends at a local Paris brasserie.[19]

Purchase [edit]

Jacques Doucet's hôtel particulier, 33 rue Saint-James, Neuilly-sur-Seine, 1929 photograph Pierre Legrain

Jacques Doucet had seen the painting at the Salon d'Antin, still remarkably seems to take purchased Les Demoiselles without asking Picasso to unroll it in his studio then that he could see it again.[69] André Breton subsequently described the transaction:

I remember the solar day he bought the painting from Picasso, who strange as it may seem, appeared to be intimidated by Doucet and fifty-fifty offered no resistance when the price was set at 25,000 francs: "Well then, it's agreed, M. Picasso." Doucet then said: "Yous shall receive 2,000 francs per month, outset next month, until the sum of 25,000 francs is reached.[69]

John Richardson quotes Breton in a letter to Doucet almost Les Demoiselles writing:

through it ane penetrates correct into the cadre of Picasso's laboratory and because it is the crux of the drama, the centre of all the conflicts that Picasso has given rising to and that will last forever....It is a piece of work which to my mind transcends painting; it is the theater of everything that has happened in the final 50 years.[78]

Ultimately, information technology seems Doucet paid thirty,000 francs rather than the agreed cost.[69] A few months after the purchase Doucet had the painting appraised at between 250,000 and 300,000 francs. Richardson speculates that Picasso, who by 1924 was on the top of the art world and didn't demand to sell the painting to Doucet, did and then and at that depression price because Doucet promised Les Demoiselles would become to the Louvre in his will. Even so, later on Doucet died in 1929 he did not get out the painting to the Louvre in his will, and information technology was sold similar virtually of Doucet'south collection through private dealers.[69]

In November 1937 the Jacques Seligman & Co. fine art gallery in New York City held an exhibition titled "20 Years in the Evolution of Picasso, 1903–1923" that included Les Demoiselles. The Museum of Modern Fine art acquired the painting for $24,000. The museum raised $18,000 toward the buy price past selling a Degas painting and the rest came from donations from the co-owners of the gallery Germain Seligman and Cesar de Hauke.[79]

The Museum of Modern Fine art in New York Urban center mounted an of import Picasso exhibition on 15 November 1939 that remained on view until 7 January 1940. The exhibition, entitled Picasso: 40 Years of His Art, was organized by Alfred H. Barr (1902–1981), in collaboration with the Art Institute of Chicago. The exhibition contained 344 works, including the major and and so newly painted Guernica and its studies, likewise as Les Demoiselles. [80]

Legacy [edit]

In July 2007, Newsweek published a two-page article about Les Demoiselles d'Avignon describing it every bit the "most influential work of art of the last 100 years".[81] Fine art critic Kingdom of the netherlands Cotter argued that Picasso "changed history with this work. He'd replaced the benign ideal of the Classical nude with a new race of sexually armed and unsafe beings."[82]

The painting is prominently featured in the 2018 flavor of the tv series Genius which focuses on Picasso's life and piece of work.

Painting materials [edit]

In 2003, an test of the painting by 10-ray fluorescence spectroscopy performed past conservators at the Museum of Modernistic Fine art confirmed the presence of the following pigments: atomic number 82 white, bone black, vermilion, cadmium yellow, cobalt blue, emerald green, and native globe pigments (such as chocolate-brown ochre) that contain atomic number 26.[83] [84]

Notes [edit]

- ^ a b c d due east Steinberg, L., The Philosophical Brothel. October, no. 44, Spring 1988. 7–74. Showtime published in Art News vol. LXXI, September/October 1972

- ^ a b c d Richardson 1991, 19

- ^ Sam Hunter and John Jacobus, Modernistic Art, Prentice-Hall, New York, 1977, pp. 135–136

- ^ Gina Yard. Rossetti, Imagining the Primitive in Naturalist and Modernist Literature, University of Missouri Press, 2006 ISBN 0826265030

- ^ a b Weschler, Lawrence (31 January 2017). "Destroy this mad brute": The African root of Globe State of war I. ISBN9781632867186.

- ^ a b John Golding, Visions of the Mod, Academy of California Printing, 1994, ISBN 0520087925

- ^ Emily Braun, Rebecca Rabinow, Cubism: The Leonard A. Lauder Collection, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2014, ISBN 0300208073

- ^ a b Picasso'due south Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, edited by Christopher Green, Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London, Cambridge University Press, 2001

- ^ a b c d e The Private Life of a Masterpiece Archived 5 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine. BBC Series 3, Episode 9. 17, eighteen

- ^ Anne Baldassari, Demoiselles d'Avignon, Pablo Picasso, Recueil des Commémorations nationales 2007, France Archives, Portail National des Archives (French)]

- ^ a b c d e f thousand Melissa McQuillan, Pablo Picasso, MoMA, Grove Art Online, Oxford Academy Press, 2009

- ^ Picasso Portrait de Allan Stein. Spring 1906 Archived nine Feb 2009 at the Wayback Motorcar. duvarpaper.com. Retrieved 27 November 2008.

- ^ Mellow, James R. Charmed Circumvolve: Gertrude Stein and Company. Henry Holt, 2003. ISBN 0-8050-7351-5

- ^ Kramer, Hilton. The Triumph of Modernism: The Art Globe, 1985–2005, 2006, Reflections on Matisse, p. 162, ISBN 0-15-666370-8

- ^ Louis Vauxcelles, Le Salon d'Automne, Gil Blas, 17 October 1905. Screen 5 and 6. Gallica, Bibliothèque nationale de France, ISSN 1149-9397

- ^ a b c d Chilver, Ian (Ed.). Fauvism, The Oxford Lexicon of Art, Oxford University Press, 2004. 26 December 2007.

- ^ Smith, Roberta. Henri Rousseau: In imaginary jungles, a terrible beauty lurks. The New York Times, 14 July 2006. Retrieved 29 December 2007.

- ^ Elderfield, 43

- ^ a b c d east f g h i j k Blier, Suzanne Preston (2019). Picasso'south Demoiselles: the Untold Origins of a Modernistic Masterpiece . Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Printing. ISBN978-1478000198.

- ^ Matisse, Henri. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 30 July 2007.

- ^ "The Wild Men of Paris". The Architectural Tape, July 2002 (PDF). Retrieved xv February 2009.

- ^ Kramer, Hilton. "The Triumph of Modernism: The Art World, 1985–2005, 2006". Reflections on Matisse. 162. ISBN 0-fifteen-666370-viii

- ^ Kramer, pp.162–163

- ^ a b Richardson 1991, 43

- ^ Richardson, John. A Life of Picasso, The Cubist Rebel 1907–1916. pp. 24–26, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1991. ISBN 978-0-307-26665-1

- ^ Timeline. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 20 April 2009.

- ^ "The Vision of Saint John". Metropolitan Museum of Fine art. Retrieved 18 February 2009.

- ^ Horsley, Carter B. The Shock of the Old. The Urban center Review, 2003. Retrieved 2 April 2009.

- ^ Johnson, Picasso'southward Demoiselles d'Avignon and the Theater of the Absurd. 102–113

- ^ Richardson, J. Picasso's Apocalyptic Whorehouse. twoscore–47

- ^ Richardson 1991, 430

- ^ D. de la Souchère, Picasso à Antibes, fifteen

- ^ Green, 45–46

- ^ Cooper, twenty–27

- ^ Cooper, 24

- ^ a b Joann Moser, Jean Metzinger in Hindsight, Pre-Cubist works, 1904–1909, The University of Iowa Museum of Art, J. Paul Getty Trust, University of Washington Press 1985, pp. 34-42

- ^ Frèches-Thory, Claire; Zegers, Peter. The Art of Paul Gauguin. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1988. pp. 372–73. ISBN 0-8212-1723-2

- ^ Edgeless, 27

- ^ Gauguin at the Salon d'Automne, 1903

- ^ Gauguin retrospective at the Salon d'Automne, 1906

- ^ Sweetman, 563

- ^ Richardson 1991, 461

- ^ Sweetman, 562–563

- ^ Richardson 1991, 459

- ^ Duerden, Dennis (2000). The "Discovery" of the African Mask. pp. 29–45.

- ^ Light-green is careful to utilize the two terms together throughout his give-and-take, 49–59

- ^ Light-green, 58–9

- ^ Picasso's words were transcribed by Fels F., "Opinions sur l'art nègre". Action, Paris, 1920; and Daix, P. "Il due north'y a pas d'fine art nègre dans les Demoiselles d'Avignon". In Gazette des Beaux-Arts Paris, October 1970. Both are quoted in Anne Baldassari, "Corpus ethnicum: Picasso et la photographie coloniale", in Zoos humains. De la Vénus hottentote aux reality shows, Nicolas Bancel, Pascal Blanchard, Gilles Boëtsch, Eric Deroo, Sandrine Lemaire, Edition La Découverte, 2002. 340–348

- ^ Richardson 1991, 451

- ^ Barr 1939, 55

- ^ Daix, Pierre. "Il n'y a pas d'art nègre dans les Demoiselles d'Avignon". Gazette des Beaux Arts, Paris, Oct 1970. 247–70

- ^ Greenish, 2005, discusses the visit, and also postcards of African people owned by Picasso. 49–58

- ^ "A magical meet at the root of modern fine art". The Economist, 9 February 2006

- ^ Edwards & Woods, 162

- ^ Richardson 1991, 34

- ^ Richardson 1991, p. 27

- ^ Miller, Arthur I. (2001). Einstein, Picasso: Infinite, Time, and the Beauty That Causes Havoc. New York: Basic Books. p. 171. ISBN978-0-465-01860-4.

- ^ Miller (2001). Einstein, Picasso. pp. 100. ISBN978-0-465-01859-8. Miller cites:

- Salmon, André (1955). Souvenir sans fin, Première époque (1903–1908). Paris: Éditions Gallimard. p. 187.

- Salmon, André (1956). Souvenir sans fin, Deuxième époque (1908–1920). Paris: Éditions Gallimard. p. 24.

- Crespelle, Jean-Paul (1978). La Vie quotidienne à Montmartre au temps de Picasso, 1900-1910. Paris: Hachette. p. 120. ISBN978-2-01-005322-i.

- ^ Décimo, Marc (2007). Maurice Princet, Le Mathématicien du Cubisme (in French). Paris: Éditions L'Echoppe. ISBN978-2-84068-191-five.

- ^ Miller (2001). Einstein, Picasso. pp. 101. ISBN978-0-465-01859-8.

- ^ Jouffret, Camaraderie (1903). Traité élémentaire de géométrie à quatre dimensions et introduction à la géométrie à n dimensions (in French). Paris: Gauthier-Villars. OCLC 1445172. Retrieved 6 February 2008.

- ^ Miller. Einstein, Picasso. pp. 106–117.

- ^ Richardson 1991, 47, 228

- ^ Gelett Burgess, "The Wild Men of Paris, Matisse, Picasso and Les Fauves", The Architectural Tape, May 1910

- ^ Cahiers d'art : bulletin mensuel d'actualité artistique, 1927 (N1,A2)- (N10,A2), Gallica, Bibliothèque nationale de France

- ^ Richardson 1991, 45

- ^ Rubin, 43–47

- ^ Daniel Henry Kahnweiler, The Rise of Cubism, New York, Wittenborn, Schultz. This is the offset translation of the original German text entitled Der Weg zum Kubismus, Munich, Delphin-Verlag, 1920

- ^ a b c d e f g Monica Bohm-Duchen, The Private Life of a Masterpiece, University of California Press, 2001, ISBN 9780520233782

- ^ a b Lettres & Art, Cubistes, Le cri de Paris, 23 July 1916, p. 10, A20, No. 1008, Gallica, Bibliothèque nationale de France

- ^ Fluegel, 223

- ^ Franck, 100

- ^ Lemke, 31

- ^ a b Berger, John (1965). The Success and Failure of Picasso. Penguin Books, Ltd. pp. 73–77. ISBN978-0-679-73725-4.

- ^ Rubin (1994), xxx

- ^ [1] Leo Steinberg selections, http://world wide web.artchive.com. Retrieved 24 February 2009.

- ^ Richardson John. A Life of Picasso. The Prodigy, 1881–1906, Dionysos p. 475. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1991. ISBN 978-0-307-26666-8

- ^ John Richardson, with Marilyn McCully, A Life Of Picasso The Triumphant Years, 1917–1932, Albert A. Knopf 2007, p. 244, ISBN 978-0-307-26666-8

- ^ Fluegel, 309

- ^ Fluegel, 350

- ^ Plagens, Peter. Which Is the Almost Influential Work of Art of the Last 100 Years?, Art, Newsweek, 2 July/9 July 2007, pp. 68–69

- ^ Cotter, Holland (10 Feb 2011). "When Picasso Changed His Tune". New York Times . Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- ^ Les Demoiselles d'Avignon: Conserving a modern masterpiece, Website of Museum of Modernistic Art, New York

- ^ Pablo Picasso, 'Les Demoiselles d'Avignon' ColourLex

References [edit]

- Blier, Suzanne Preston. "Picasso'south Demoiselles: The Untold Origins of a Modern Masterpiece." Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press. 2019.

- Edgeless, Anthony & Puddle, Phoebe. Picasso, the Determinative Years: A Study of His Sources. Graphic Society, 1962.

- Cooper, Douglas. The Cubist Epoch. Phaidon Press, in clan with the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1970. ISBN 0-87587-041-four

- Edwards, Steve & Wood, Paul. Fine art of the Avant-Gardes: Fine art of the Twentieth Century. New Oasis: Yale University Press, 2004. ISBN 1478000198

- Everdell, William R., Pablo Picasso: Seeing All Sides in The Commencement Moderns, Chicago: University of Chicago Printing, 1997

- Fluegel, Jane. Chronology. In: Pablo Picasso, Museum of Modern Art (exhibition catalog), 1980. William Rubin (ed.). ISBN 0-87070-519-9

- Franck, Dan. Bohemian Paris: Picasso, Modigliani, Matisse, and the Birth of Modern Fine art. Grove Press, 2003. ISBN 0-8021-3997-three

- Golding, J. The Demoiselles d'Avignon. The Burlington Magazine, vol. 100, no. 662 (May 1958): 155–163.

- Dark-green, Christopher. Picasso: Architecture and Vertigo. New Haven: Yale Academy Press, 2005. ISBN 0-300-10412-Ten

- Dark-green, Christopher, Ed. Picasso's Les Demoiselles D'Avignon. Cambridge University Press, 2001. ISBN 0 521 583675 PDF

- Klüver, Billy. A Day with Picasso. The MIT Press, 1999. ISBN 0-262-61147-iii

- Kramer, Hilton,The Triumph of Modernism: The Art Earth, 1985–2005, 2006, ISBN 0-15-666370-8

- Leighton, Patricia. The White Peril and L'Art nègre; Picasso, Primitivism, and Anticolonialism. In: Race-ing Fine art History. Kymberly N. Pinder, editor, Routledge, New York, 2002. Pages 233–260. ISBN 0-415-92760-9

- Lemke, Sieglinde. Primitivist Modernism: Black Civilisation and the Origins of Transatlantic Modernism. Oxford: Oxford University Printing, 1998. ISBN 0-19-510403-X

- Richardson John. A Life of Picasso. The Prodigy, 1881–1906. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1991. ISBN 978-0-307-26666-8

- Richardson, John. A Life of Picasso, The Cubist Rebel 1907–1916. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1991. ISBN 978-0-307-26665-1

- Richardson, John. A Life of Picasso The Triumphant Years, 1917–1932. New York: Albert A. Knopf, 2007. ISBN 978-0-307-26666-8

- Rubin, William. Pablo Picasso A Retrospective. MoMA, 1980. ISBN 0-87070-519-9

- Rubin, William. Picasso and Braque: Pioneering Cubism. HNA Books, 1989. ISBN 0-8109-6065-6

- Rubin, William. Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. MoMA, 1994. ISBN 0-87070-519-ix

- Rubin, William, Hélène Seckel & Judith Cousins, Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, NY: Museum of Mod Art/Abrams, 1995

- Sweetman, David. Paul Gauguin, A life. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995. ISBN 0-684-80941-nine

External links [edit]

- Les Demoiselles d'Avignon in the MoMA Online Collection

- Les Demoiselles d'Avignon Conserving A Modern Masterpiece

- Julia Frey, Anatomy of a Masterpiece, New York Times Review of Les Demoiselles d'Avignon Past William Rubin, Helene Seckel and Judith Cousins

- Gelett Burgess, The Wild Men of Paris, Matisse, Picasso and Les Fauves, 1910 (PDF)

- Pablo Picasso, 1907, Five Nudes (Study for "Les Demoiselles d'Avignon"), watercolor on wove paper, 17.5 x 22.5 cm, Philadelphia Museum of Art

Les Demoiselles D'avignon Color Scheme,

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Les_Demoiselles_d%27Avignon

Posted by: sancheznernat.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Les Demoiselles D'avignon Color Scheme"

Post a Comment